From the Anthology

Sustaining Service: 2025 Veterans' Anthology

“One!”

BANG!

“Two!”

BANG!

“Three!”

BANG!

Slamming kitchen cupboard doors echo throughout the house and out the windows into the Ohio afternoon, alerting young Frankie, searching out in the garage.

His dad, Big Frank, punctuates his word count with each collision, calling the attention of all players. It’s game time, play ball.

“One!”

BANG!

“Two!”

BANG!

“Three!”

BANG!

Big Frank wonders how his kids lack the gumption to shut the doors they’ve opened–has found the only way to confront negligence.

“One!”

BANG!

“Two!”

BANG!

“Psssst. Close those doors.” Frankie whispers to his friend as he points towards the metal garage cabinets.

They quietly close the doors left ajar. The screen door spring rattles, warning the boys that Big Frank is about to pick them off.

“What don’t you have that you think you should have?” It’s his opening pitch, a verbal slider.

Leaning in from his three-step mound, Big Frank peers downward, scanning the garage in search of any possible lead off.

Frankie, caught with his hand poised in midair, takes a tentative swing.

“I’m, eh, looking for my ball glove.”

It’s strike one as Frankie resumes routing through a crate filled with old baseball equipment.

Across the street is Durling Park, built in 1920 on the remains of an abandoned spur line railroad that once linked the coal mines with the Erie Railroad mainline. It includes a wooded ravine, a remnant glacial creek bed, sturdy playground equipment, a brick pavilion, four tennis courts and the ballfield, home of baseball games for every age.

It’s 1957, Ohio; playing baseball is part of every hot summer afternoon.

Every day, boys show up early to choose sides, using the time-tested method of tossing a bat into a waiting hand, walking hand over hand until at last one thumb wraps over its end. They set the batting orders and assign positions with special considerations for the kids that survived the polio epidemic.

Eddie can hit the ball all the way to the fence, but he cannot run. Jeff is so fast he’s not allowed to steal. Joe can hit a homer with the flick of his wrist so “over the fence is out” for him.

Boys control this process without adult supervision even as Alice looks and listens from her open kitchen window, alert to any signs of mayhem or hooliganism.

“You kids go out and play,” Alice’s morning reveille begins the day.

In 1948, when Big Frank and his young wife Alice bought the house, the park was attractive for their young family. That appreciation waned as Ohio’s summer winds blew dust clouds into Alice’s laundry and the baby Frankie was woken by the clanging of late night horseshoe matches. The church league softball games too often stretched until the last vestige of sunlight waned, providing even more frustration.

As Frankie’s independence grew, he led late night raids to the park in search of contraband left behind. This crate in the garage, where it all ends up, is a storehouse of balls, bats and a few gloves that keep the afternoon’s games going. Whiskey bottles left from the church games provide evidence for Big Frank’s periodic trip to City Hall to complain. It’s an exercise in futility.

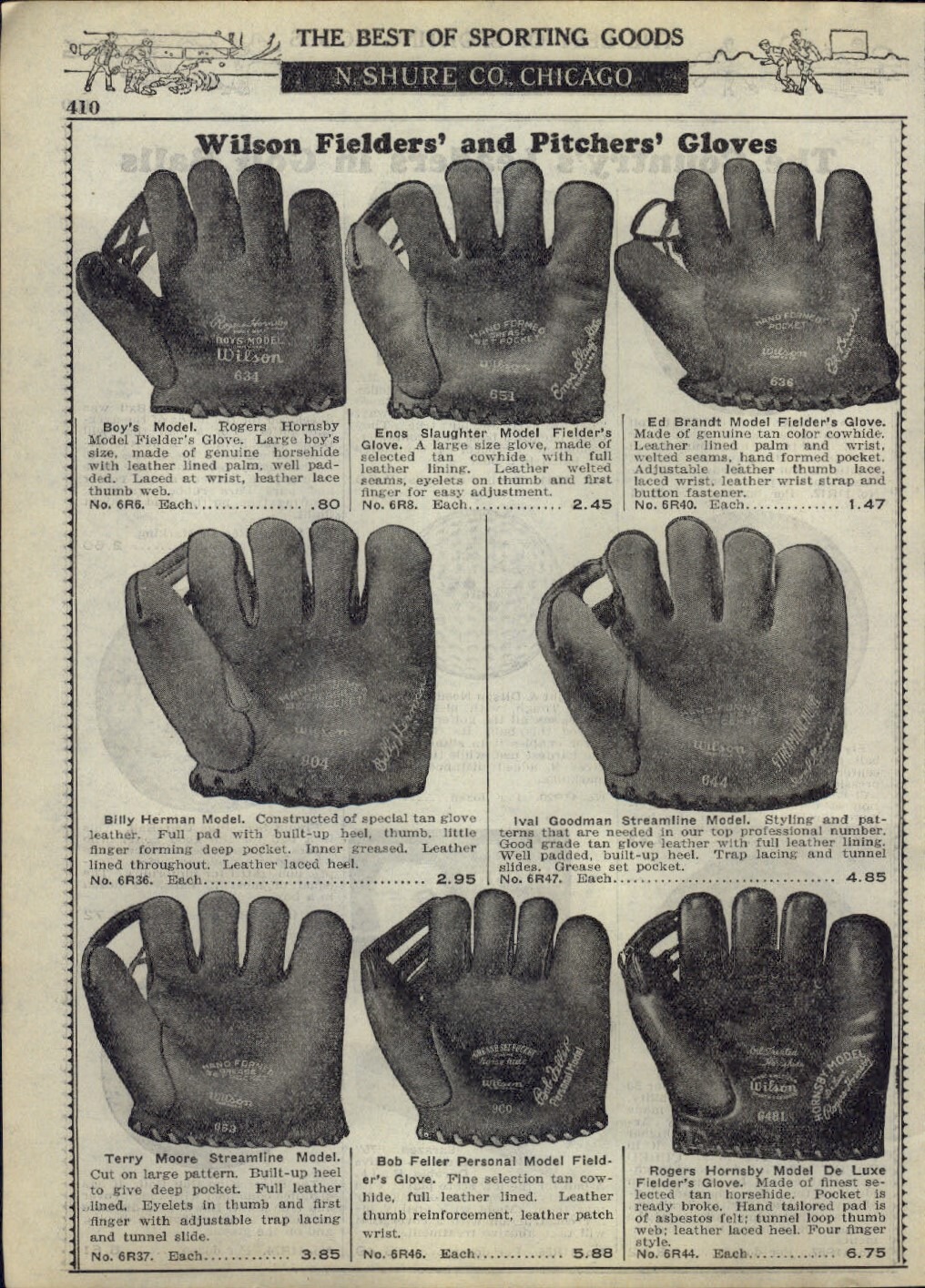

Frankie’s current search turns up nothing but a flat leather glove with four fingers and no stitching.

“What’s wrong with this mitt?”

Big Frank’s choice of words is calculated as he slips the late 1930s baseball mitt on his man-sized hands, squeezing it to form a shallow depression in its palm.

He questions the existence of something called a baseball glove, let alone it being something necessary to play baseball.

He offers up his second pitch.

“This is a good mitt.”

Is this strike two?

The game might as well be over as Big Frank digs into his repertoire of available pitches.

“I can’t play with this thing,” Frankie tugs the leather onto his hand.

“There’s no pocket.”

It’s strike two.

“Sure, there is.”

His dad opens a cupboard grabbing a bottle of Neatsfoot Oil, closing the door with deliberate care. He rubs a dollop into the worn leather with bare fingers, restoring its shine, revealing the embossed name, Terry Moore Model on its heel.

“It’s a good mitt.”

Big Frank admires the treasure.

“How can I catch a ball with this?” Frankie swings.

He tries to pick up an old brown baseball.

“It can’t even hold onto a ball.”

Big Frank, recognizing his son's vulnerable stance, prepares his final pitch, the coup de grâce.

It’s his fastball, and he’s Bob “Rapid Robert” Feller.

“You use two hands to catch a ball.”

He delivers the pitch.

Frankie takes it. Not fooled in the slightest, he resumes rummaging, careful to avoid disrupting Big Frank’s system of organization. “I want my glove.”

“Where does it belong?” Big Frank responds with his ultimate pitch, a change up, a seductive pitch inviting an ill-timed swing.

Any answer admits timely awareness and concedes responsibility for the location of any missing item. Frankie knows that his father knows exactly where the glove is because he put it there, where it belongs.

Frankie protests the game.

“Did you put it somewhere?”

“What?” Big Frank’s response resonates.

It’s not so much the word itself as the windup and delivery of this final pitch.

He shrugs it off as if he didn’t hear you the first time.

“What?”

Dancing like a knuckleball it drops in to close the game.

“What” is little more than a deflection. He knows what you want and will reveal that only when the ball is finally in the catcher’s mitt.

“Bang! Strike three.”

Big Frank picks up a ball and an old catcher's mitt that has aged into a leather pillow.

Pounding the ball into the relic, he walks towards the ball field, turning to toss the ball to Frankie.

“Pitch it cheer, my ma’s lookin’.”

Why not?

It’s a good mitt.

----------

Douglas Kulow served in the US Army in 1966-69 as a crypto graphics technician in the 1st Signal Brigade in the Vietnamese central highlands as well as Forts Benning, Monmouth, Jackson, and Leavenworth. After serving, he returned to college and began working as a family therapist. He went on to become Administrator of Children's Services in Holmes County and after retirement taught high school as a substitute. Living in Wadsworth, Ohio, he has four adult children and four young grandchildren. Today, he writes short stories and poetry, and (of course) he is working on his own great American novel.